CALIFORNIA Magazine | April 21, 2014

When 29-year-old UC Berkeley student Ophir Bruck spotted Sherry Lansing, the former CEO of Paramount Pictures, on her way to a University of California Regents meeting, he was holding on to a key that he hoped she wouldn’t refuse.

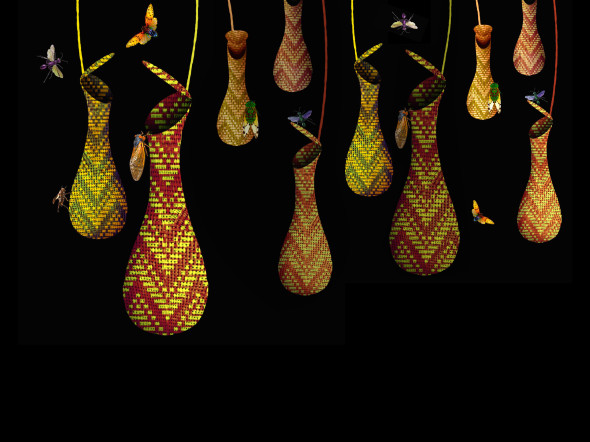

“We’re here to call on the UC Regents to take bold action on climate change,” Bruck told Lansing last May, as she walked past 58 chanting students chained to two homemade structures designed to represent oil drilling rigs. “Will you symbolically unlock us from a future of fossil fuel dependence and climate chaos?”

“I drive a Prius,” Lansing replied, without stopping.

But now the issue is coming to a head at the University of California system, as activists push hard for it to become the nation’s first large public research institution to jettison fossil fuel investments. Over the coming months, the UC Board of Regents—trustees of a $6.4 billion endowment, one of higher education’s greatest—will be forced to grapple with the question.

As climate change accelerates faster than ever before—and with the world’s top oil, gas and coal companies already controlling a tremendous amount of fossil fuels—college students all over the country are urgently pressuring universities to divest their holdings of these corporations. Thus far 10 U.S. colleges and universities have committed to divest, and the movement is active on 450 campuses nationwide. To date, over 60 more entities (mostly municipalities, churches and foundations) have heeded the call to divest, attributing their actions in part to a desire to leave a world that future generations will be able to inhabit.

But it has particular frisson at UC Berkeley, where on Monday student activists dressed in black kicked off Earth Week 2014 by lying down in Dwinelle Plaza to simulate a “human oil spill”—and to demand the UC system divest itself of fossil fuel companies. With historically successful divestment campaigns targeting then-apartheid South Africa, tobacco companies and Sudan, Cal students have been catalysts for turning financial calculations into moral ones.

“If we do not divest from fossil fuels, and continue business as usual, future UC students will not have livable futures—and it’s part of the Regents’ fiduciary duty to ensure that they do,” says 21-year-old UC Berkeley junior Victoria Fernandez, one of Fossil Free Cal’s campaign leaders.

Student activist Victoria Fernandez chained herself to a mock oil rig as a protest against UC fossil fuel investments at a May 2013 Board of Regents meeting in Sacramento, Calif.

Fernandez, an environmental studies major, has made her cause consistently visible to the Regents over the past year. She repeatedly turns up at their meetings to give public comments, was one of the 58 chained to the oil rig, and regularly tries to engage the throng of students rushing through Sproul Plaza to join divestment efforts.

She’s motivated by her father, the son of a braceros agricultural worker from Zacatecas, Mexico who labored on a date farm in Indio, Calif. “My dad never wanted to waste anything and recycled everything—those values were cemented in me growing up,” she said. When her father immigrated to the U.S. at the age of 5, the family lived in the one tiny shack sitting in the midst of a huge stand of palm trees.

Bruck, an environmental studies re-entry student who is poised to graduate next month, says that divesting presents transformational promise for society. “It’s more than about just reducing carbon emissions—it’s a justice issue,” he says. “It’s an opportunity to rethink outdated political, economic and social systems out of which the crisis was born.”

While UC has been listening to what Fernandez and Bruck are saying about the need to divest, it’s not fully convinced. UC Regent Bonnie Reiss—who served as a climate advisor to former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger—and UC Chief Financial Officer Peter Taylor question the benefits of divestment from a portfolio tasked with bringing in returns to support faculty research and student scholarships, as well as whether divestment would actually weaken the industry at all.

“UC’s mission is not just to fight climate change—our primary mission is access and affordability to receive a great education,” Reiss says. “So it should be a really rare incident where you’re putting any restrictions on your investment criteria that are anything but maximizing your return on investment.”

Both Reiss and Taylor point to the UC’s decision to divest from tobacco stocks in 2001 as proof of such risk. Each year, the university system analyzes how the portfolio would have performed had it not divested. During the 2012-2013 fiscal year, the portfolio earned $44.9 million more without the tobacco stocks.

But when looking at its cumulative difference calculated between the portfolio and its hypothetical alter ego between 2001-2013, the portfolio lost $471.6 million. “Are tobacco companies any less vibrant since 2001?” Taylor asks. “I don’t think it’s appropriate for staff members make value judgments on whether we should invest in tobacco companies, if genetic engineering is good or bad, if fossil fuels are good or bad. Where do you draw the line? What’s the answer to that? I’d love to know.”

Back in 2011, a divestment campaign targeting a select group of coal companies failed to take off on campus. But a broader initiative gained momentum last spring, a few months after climate activist Bill McKibben spoke at Berkeley as part of a national tour to rally supporters around the campaign organized by his nonprofit organization 350.org. Its call: Institutions should divest from the top 200 oil, gas and coal companies.

Bruck was in the crowd that evening—one of just 15 to 20 students among a few hundred people, he observed, when McKibben asked all the students in the room to stand up.

“He called upon us, saying that you have the power to take action and to leverage your position as students and push your institutions to act on climate,” Bruck says. “The whole presentation—it gets you mad, it gets you scared. Not fearmongering-scared, but realistically concerned about everything you care about.”

350.org’s argument is based on research showing that if the top companies burned all of their reserves, it would raise the earth’s temperature beyond 2 degrees Celsius—the amount that governments agreed not to exceed collectively in the international climate agreement brokered at Copenhagen in 2009. Anything beyond this threshold, U.N. climate scientists predict, will create a world of heat waves, unprecedented sea-level rise and not enough food and water to support an increased population of nine billion people by 2050. Recently, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a report concluding that greenhouse gas emissions need to be cut from 40 to 70 percent by midcentury in order to prevent a climate catastrophe.

And according to Carbon Tracker, the London-based think tank that conducted the top 200 companies research, these corporations have five times more carbon to burn than the amount that would keep the earth below the two-degree limit.

After McKibben addressed the students, Bruck recalls feeling a responsibility to take action, though he had never really committed himself to organizing on an issue before. “Things in my life culminated where I was ready to engage myself at this moment—and climate change was not one of those issues until I came out of that talk,” he says.

Students try to catch the attention of UC campus chancellors and the Board of Regents outside its May 2013 meeting in Sacramento, Calif.

Students at Cal and other UCs adopted 350.org’s call for action. They began asking the Regents to divest $11.2 billion (a $6.4 billion general endowment pool and an additional $4.8 billion sitting in campus endowments) from these top 200 companies within five years of making the commitment. Their kickoff rally was at the Regents’ Sacramento meeting last May, when they chained themselves to the symbolic oil rig, chanted calls for divestment and gave a 15-minute speech to the regents via 15 students speaking one minute at a time, so as not to violate the one-minute public comment limit.

In January, after Fernandez and Bruck discussed the issue with a group of Regents over lunch, the Regents agreed to set up a task force comprised of students, Regents and faculty that would examine the issue and bring its findings to the Regents’ Committee on Investments. The task force would then make a recommendation to the committee, which would in turn make their recommendation to the full body of Regents. Finally, Regents would vote on whether to divest its endowment.

“It’s the same process that the Regents went through before voting to divest from Sudan in 2006,” says Bruck.

But unlike the Sudan divestment—one that involved just nine companies—oil, gas and coal companies are a trickier and more pervasive proposition. Taylor estimates that of the university system’s $6.4 billion general endowment holdings, “just north” of $100 million are invested in fossil fuel stocks.

“It’s not impossible, but it’s an uphill battle for the Regents to approve this,” says Reiss. “We need to analyze the true costs and benefits.”

She contends that UC initiatives such as its green building requirements, and UC President Janet Napolitano’s goal to get the nine-campus system carbon neutral by 2025, are more effective ways to fight climate change. Green construction, she says, not only reduces carbon emissions, but also creates markets for sustainable building materials and clean technology.

Students such as Fernandez and Bruck admit that if UC decides to divest from fossil fuels, it would be a symbolic gesture and probably not make an impact on the huge corporations’ bottom lines. But they insist there is more to gain by changing public opinion.

“At the end of the day, we’re trying to stigmatize the fossil fuel industry and take away their social license to operate,” Fernandez says. “The harmful things fossil fuel companies do to communities are not seen by the economy and the world as a whole. They hurt them economically and health-wise. Look at Chevron in Richmond.”

Creating that social stigma has worked before. Although UC Regents and Berkeley chancellors initially resisted thousands of anti-apartheid activists pushing for divestment from South Africa, the university system did so in 1986 after 18 months of demonstrations and physical confrontations between protestors and campus police, anti-apartheid activist and Berkeley alumni Steve Masover has recalled. In 1990, Nelson Mandela credited the Berkeley movement with playing a significant role in the downfall of apartheid.

Bruck is bracing for the long haul. After graduation, he says, he can see himself continuing to do climate change organizing full-time.

CEO Andrew Behar of As You Sow, an Oakland-based shareholder activist group, sees another compelling financial reason to divest. He’s among a growing group of investors warning of the risk of investing in fossil fuel companies because of the “carbon bubble”—the idea that the value of fossil fuel stock is overpriced. The theory goes like this: If governments pass climate regulations or carbon taxes to prevent the earth’s temperature from rising beyond 2 degrees Celsius, fossil fuel companies will be forced to leave most of their reserves in the ground. To keep that temperature threshold, according to a 2013 study by Carbon Tracker, only 20 to 40 percent of those reserves could be burned.

Behar estimates the value of the carbon bubble, or the industry’s “stranded assets,” as they’ve also been dubbed, to be $20 trillion. He says that in the last year, the bubble has already started to burst as coal has been dumped in favor of natural gas and renewable energy sources.

“Nine coal companies went bankrupt last year. If you bought coal two years ago, you lost 58 percent of their portfolio’s original value,” he says. “It’s moving more rapidly even than anyone thought possible.”

In March, in a response to pressure from activists, ExxonMobil released a report to shareholders that concluded “we are confident that none of our hydrocarbon reserves are now or will become ‘stranded.’ We believe producing these assets is essential to meeting growing energy demand worldwide, and in preventing consumers—especially those in the least developed and most vulnerable economies—from themselves becoming stranded in the global pursuit of higher living standards and greater economic opportunity.”

Out of the 10 colleges that have chosen to divest in fossil fuels, most are small and private. The largest was Pitzer College, which announced on April 12 (via trustee Robert Redford) its decision to divest its $130 million.

There’s a reason why no large public institution has stepped into the ring thus far. “Many universities remain unwilling to risk their endowments and need, frankly, more certainty,” says Taylor, citing an op-ed by the University of Michigan’s Chief Investment Officer Erik Lundberg arguing that divestment was impractical.

And with a $32.7 billion endowment—the largest treasure chest among all U.S. colleges and universities—Harvard President Drew Faust emphatically dismissed divestment, citing concerns that the university would inappropriately appear to be a “political” actor, as well as risk future returns. (Recently, the university signed on to UN-backed principles for “responsible investment.” That is a non-binding framework, which critics see as an empty gesture).

But those who have studied the impacts of fossil fuel divestment—as well as at least one college that divested—refute the idea that it will inevitably lead to financial losses.

“Our analysis found that if you are doing market cap weighted indexing, there is very little cost to divestment from a risk standpoint,” said Liz Michaels of Aperio Group, a Sausalito, Calif.-based investment management firm specializing in value-based investing. The company doesn’t maintain a position on fossil fuel divestment.

Aperio—which subscribes to the philosophy that investors can only match the market, not beat it—used Barra proprietary software to remove a portfolio’s holdings in the fossil fuel sector, then asked it to reinvest and reweight them to match market performance as much as possible.

“We’ve done much better after divestment,” said Stephen Mulkey, the president of Unity College in Maine, which divested in November of 2012. “We’ve achieved significant gains because we are paying closer—almost daily—attention”—a constant watch of its portfolio funds to ensure that fossil fuel holdings stay below 1 percent of the college’s endowment. The college also invests all proceeds from the fossil fuel holdings into an internal fund that provides financing for energy efficiency, renewable energy, or other sustainability projects, with the money saved then invested back into the fund.

The UC Regents’ Committee on Investments Task Force has yet to be convened. At last month’s Regents meeting, Fernandez and Bruck dutifully waited their turn to speak at the public comment session and remind the assembled group of the task force’s importance. Still, the students say that a vote on divestment is possible within the year; Taylor says a Regents discussion by November is realistic.

Many divestment backers simply advocate switching from fossil fuel holdings to cleantech and green bond holdings. But Berkeley energy professor and divestment advocate Daniel Kammen, a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, says it’s also important to draw on the expertise of the oil, gas and coal companies, spurring them to help create an economy that does not rely on fossil fuels.

“In the transition to renewable energy, we need to move them from extractive companies to knowledge-based companies,” he says. “There are more people that are really well versed in technology and economic policies in the big energy companies than anywhere else. So it would be crazy not to forge partnerships with them and build on their resources.”

All photos of Fossil Free UC action at University of California Board of Regents Meeting by Mauricio D. Castillo

View the original story here.