Modern Farmer | Nov. 10, 2015

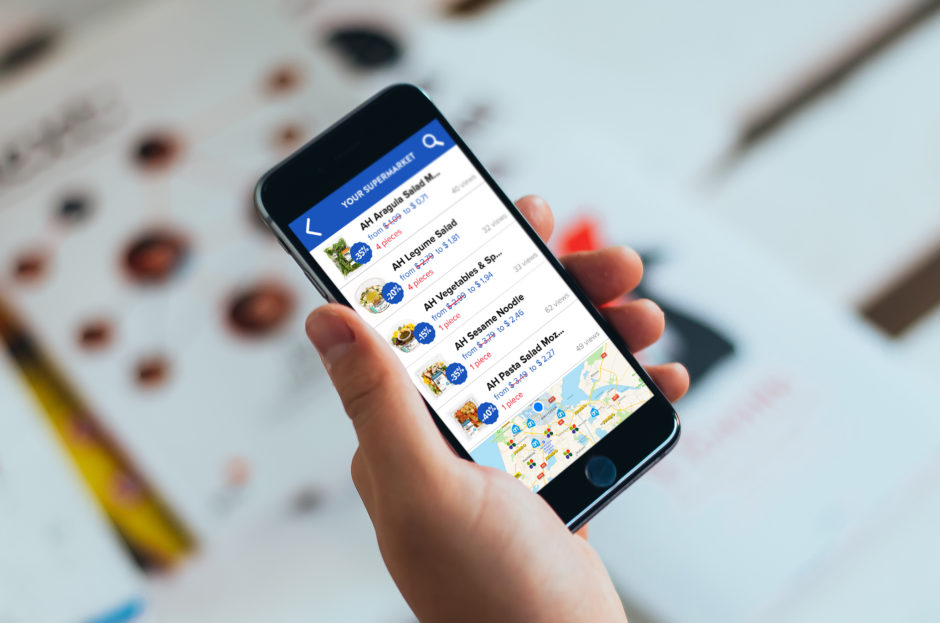

Inside BioConsortia’s research facility, where plants are being tested in a variety of soils. (Photo credit: BioConsortia)

We talked with BioConsortia, an agricultural biotech company headquartered in Davis, Calif., that’s using a recently patented way to identify the specific combination of plant microbes to help improve crop yields in corn, wheat, and soybeans. It says that by 2017, it will be able to commercialize its first seed treatments containing the microbe combo that would enable a plant use less fertilizer yet get comparable yields.

The technology seems like what a plant breeder might do if collaborating with a microbiologist on speed.

One skeptic points out that it can be difficult to grow and mass produce such a group of microbes in the lab, so it’s not a done deal. Other companies—such as Novozymes and Monsanto—are also working with microbes. If it all pans out, it could change the face of agriculture as we know it by providing farmers with a natural alternative to genetically modified corn, soy, and wheat.

The process, dubbed Advanced Microbial Selection (AMS), inspired Khosla Ventures to invest millions in two rounds of BioConsortia’s R&D funding over the last four years. AMS scouts out each crop’s “dream team” of five to seven microbes, or microscopic organisms, that work together to boost a plant’s growth. (These microbes live both within the plant and in the soil.)

The technology seems like what a plant breeder might do if collaborating with a microbiologist on speed.

“It turns the traditional model—where microbiologists test microbes one by one—on its head,” says BioConsortia’s CEO Marcus Meadows-Smith. A serial biotech executive with a background in business and genetics, Meadows-Smith joined BioConsortia after a stint as the head of Bayer’s biological pest management division.

Here’s how the process (which was just patented last month) works, according to Meadows-Smith: First, scientists seek out the best-performing plants living in a variety of soil environments around the world, including ones stressed by drought, desert, cold, and wet conditions. Then they conduct DNA sequencing of the plants and the soils to determine what kinds of microbes are present.

Next, back in Bioconsortia’s California growth chambers, they root these plants in their original soils, then into normal and stressed soils. After observing which plants are thriving and which are faring poorly, they conduct another DNA sequencing round in the plants and the surrounding soils. The purpose is to identify all of the microbes hanging around. Some help to speed up growth by making nutrients more accessible, while others can defend against pathogens that might be present. (Think of the group as being there to help and protect—like a celebrity entourage of personal assistants and bodyguards.)

By looking closely at that entourage of microbes (collectively known as the plant’s microbiome), and comparing which specific microbes are present in the plants that are doing well with the ones those that are faring the worst, BioConsortia says it can nail down each crop’s “dream team” for each soil environment tested.

“We’re looking for that unique combination to keep the plants healthy—even with the ability to recover from drought and staving off the effects of a pathogen,” Meadows-Smith said. “The beneficial microbes have not been documented over the years, compared to the pathogens.”

To date, the company has performed experiments on corn, soybeans, and wheat. It’s in its second year of independent/third-party field trials that are testing the seed treatments (comprising the microbial “dream teams”) it has manufactured for these crops.

But even though Meadows-Smith says that the first year of field trials show that its approach increases yield by 6 percent (compared to an average of an <2 percent increase in yield for a genetically modified or hybrid approach) and a double-digit increase in stressed crops, he declined to show results or provide more details to Modern Farmer, citing confidentiality agreements.

Meadows-Smith says that the improved varieties include corn that produce greater yields, utilize fertilizer more efficiently, and are more drought tolerant, as well as wheat and soy that produce more. In the coming months, BioConsortia will start field tests for tomatoes and leafy vegetables.

“Using microorganisms is definitely the way of the future as it’s more environmentally sustainable [compared to using chemicals],” says Kari Dunfield, a professor of soil ecology at Ontario’s University of Guelph, who studies how agricultural practices affect microbial communities in soils. “The approach makes sense, as we know that microorganisms interact with each other and are synergistic.”

But the expert does express some reservations about BioConsortia’s process. “We know that it’s still really hard to grow those organisms in the lab, so that step will be tricky,” Dunfield says. “It’s one thing to know what organisms are there with the DNA, but when you have the DNA you don’t have enough to grow the organism, so that’s the rate-limiting mechanism.”

She also points out that since microbes are living organisms, they’re unpredictable—which adds a more complex aspect to production compared to working with chemicals. “When you’re selling a mixture [of microbes], you have to make sure they’re not outcompeting each other when you sell it to the farmer.”

A few years from now, Meadows-Smith wants to use Advanced Microbial Selection method to address food security for a growing world population.

But Meadows-Smith insists that BioConsortia’s approach could save millions of dollars. He says it takes $25 million to bring a microbial seed treatment to market, $60 million to do the same for a biopesticide (due to the global registration process), and $135 million for genetically modified trait (according to Peter W.B. Phillips, a professor of public policy at the University of Saskatchewan).

Advanced Microbial Selection can also speed up the research phase, Meadows-Smith claims, so products can get to market in about five years, compared to DuPont’s estimate of the 13 years it takes genetically modified crops to get to market.

“There is a long R&D phase [for GM crops], followed by field trials, field multiplication, and registration,” he said.

Meadows-Smith says that scientists first came up with the idea five years ago at BioDiscovery (BioConsortia’s subsidiary company in New Zealand) while conducting contract research for companies like Syngenta, Monsanto, and Bayer. “They had brainstorming sessions to find ways to improve the speed and efficiency of their discovery process,” Meadows-Smith said. “It was to this end that they had the breakthrough to think of this as a plant phenotype (or plant breeding question) and solution rather than a microbial question.”

He cites more dramatic numbers: The company screens 100,000 microbes in nine months, he says, while a conventional approach would take three to four years.

BioConsortia wants to sell the microbial seed treatments (which are applied directly to the seed) to distributors. If all goes well with the second year of field trials, Meadows-Smith says that a biofertilizer seed treatment—one that would need less fertilizer for comparable yields—will be commercialized by 2017.

But he doesn’t think the approach will necessarily replace other methods—such as genetic modification—across the board.

Currently, the company is focusing on the in the European and North American market. Next, Meadows-Smith says he wants to expand BioConsortia’s efforts to Latin America, Brazil and Argentina.

And a few years from now, he wants to use Advanced Microbial Selection method to address food security for a growing world population—something that’s projected to be a problem in the coming decades given stresses on the environment including drought, lack of arable land to grow sufficient amounts of food, environmental pollution, and climate change.

Meadows-Smith says that BioConsortia’s approach can develop crops that can create more harvestable yield, deposit more protein into wheat, or select for a microbiome that will improve the sugar content of plants.

“A few years from now we’d like to work on [applying this to] cassava, a staple carbohydrate for many parts of Africa,” he said.