GreenBiz | February 18, 2014

In the future, tracking the growth and development of a certain stand of açaí palm trees in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest might just as likely be done by a student as a government biologist.

That’s because a new data portal and mobile app built by IBM in its São Paulo research lab — one of 12 R&D hubs run by the company experimenting with new approaches to sustainability — will be used by a cadre of citizen scientists to help the Brazilian government monitor and track the biodiversity of the Amazon rainforest. It’s part of a group of projects developed by the company to give users the tools to help manage and monitor their environment via crowdsourced data.

In 2010, Brazil’s Ministry for Environment and Innovation presented his group with a 500-page catalog of all the species recorded in an area of rainforest close to the city of Manaus, according to Sergio Borger, a team lead of the São Paulo human systems division.

“Though this area was well explored, it comes up as just a big square on Google Maps,” Borger said. “That paper catalog of its biodiversity was limited to the scientists who created it.”

The government challenged IBM to think of ways it could bring the experience of the rainforest alive to younger generations — and simultaneously develop a central repository for all of its data.

But instead of conjuring up the hot and humid climate of the Amazon rainforest as inspiration, Borger was moved by a winter memory from 15 years ago: the time he and his children counted birds for the Audubon Society during its Christmas Bird Count. The oldest known citizen science project in the world, data from the 114-year-old count helps scientists monitor biodiversity and gain greater insight from population changes over time.

“I was very passionate about that,” he said. “So I felt crowdsourcing was the way to go, as one of the elements of monitoring our environment is asking our citizens about it.”

As the government’s first priority was to get the project into the schools, Borger and his team first prototyped a website-based platform they dubbed Wikiflora. It took them a year and half, and was completed in October 2011.

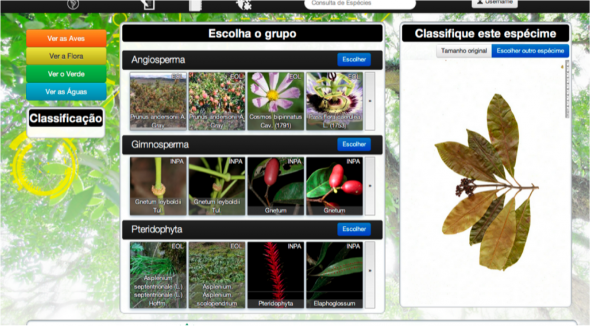

Wikiflora enabled students to upload their photos of a plant species, enter specific characteristics and classify it after comparing it against an existing catalog photo. Each photo contained data to describe precisely where it was taken.

A key part of the platform was its identification gaming function. Students could review their peers’ entries and rate how well they thought that student classified photos. A user’s rating would determine the weight of his or her assessments.

Over the next year, the team developed a mobile app, Wikiflora 2.0, which carried over the feature that allowed students to upload photos and rate them with their smartphones. It also gave them the capacity to track and map individual plants and trees, as well as components such as the leaves and trunk, via more photo uploads. To identify the particular plant or tree, students were asked to choose from a long list of similar-looking plants or trees that the app would present for selection.

But because the students were too impatient to scroll through the options, Borger said, his team set off a year ago to revamp Wikiflora 2.0 so the public could collect data and monitor it over time using real-time processing and data aggregation.

“We’re on our third wave of learning now,” he said.

The platform’s third iteration, Missions, uses the company’s IBM InfoSphere Streams product to process collected data coming in (from many sources at any particular moment) before it gets stored in a DB2 database. Borger estimates that it will be released later this year for both Android and iOS smartphones, but in a research capacity only.

Multiple users will be able to add to the data file of a specific plant or tree by using unique identifying characteristics, such as the diameter of a tree trunk.

“That can be done with some level of certainty,” Borger said. “At this point, the system makes an assumption [on which plant or tree the data belongs to], but we’re working to refine it even further.”

His São Paulo team is developing tools to advance the capability of real-time processing and aggregation of images so that when a user takes a photo of a certain element of a plant or tree, for example, Missions will help the user determine its species and give the user five to six options to choose from. After the user makes the final identification, the data is sent to the database.

Tracking mobile species, such as frogs and insects living close to water, tack on another dimension of complexity altogether. They will be included in the future, Borger says, as his team is determining how to handle this type of monitoring.

IBM is particularly interested in knowing if insects living close to water are present because they can serve as bioindicators.

“If they’re not there, the water may not have enough oxygen for them to live,” Borger said.

The company’s efforts to get the public to crowdsource environmental indicators through technology is not new territory for IBM.

In 2009, an engineer in its San Jose, Calif., Almaden Research Lab developed CreekWatch, an app where users help the state to monitor drought conditions by uploading photos and weighing in on water levels, flow rate and the amount of trash at each location. Borger applied what he learned from this project to the development of the Wikiflora and Missions platforms.

And IBM’s Accessible Way app allows the greater public to map accessibility barriers in urban areas, so that mobility-challenged individuals can select suitable routes well in advance of their trip.

“We look at sustainability,” Borger said, “as a way to make our environment smarter.”

View the original story here.

Screenshot of Wikiflora web app courtesy IBM Brazil