The Guardian US/UK | Oct. 30, 2015

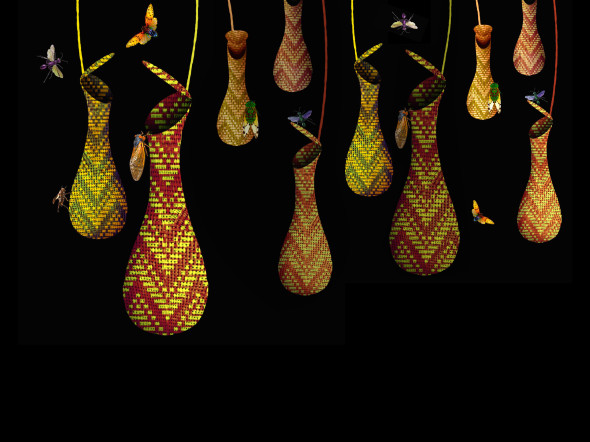

A team of Thai designers developed Jube, an insect catcher that mimics the structure of the carnivorous pitcher plant. Photo credit: Pat Pataranutaporn/courtesy of the Biomimicry Institute.

From lab-grown burgers to farms monitored by sensors and drones, technology lies at the heart of many of today’s sustainable food solutions. Now, the Biomimicry Institute, a Montana-based nonprofit, is taking the trend a step further with its new Food Systems Design Challenge, encouraging a cadre of entrepreneurs to improve the food production system by emulating techniques and processes found in nature.

At the SXSW Eco conference earlier this month, the institute announced the eight finalists in the challenge. “We want to help foster bringing more biomimetic designs to market … to show that biomimicry is a viable and essential design methodology to create a more regenerative and sustainable world,” said Megan Schuknect, the institute’s director of design challenges.

Just as natural processes often benefit multiple stakeholders, many competitors in the challenge are seeking to solve multiple problems. BioX, a finalist team from Bangkok, hopes to increase food security while helping users secure a steady source of income.

On the outside, BioX’s product, Jube, looks like a decorative hanging vase. Inside, it’s a bug trap that catches protein-rich edible insects. Lined with inward-pointing hairs that move insects downward and keep them from escaping, it mimics the structure of a pitcher plant.

“The product is designed to be artistic and crafted so that people in any community can make it and sell it to other people as an alternative source of revenue,” said Pat Pataranutaporn at the SXSW Eco Conference. Each vase is decorated with multicolored patterns designed to copy the plants’ mix of mottled colors. “We believe that we can spread biomimicry through culture and art,” Pataranutaporn said.

Easing into commercialization

By 2030, bioinspired innovations could generate $1.6tn of GDP worldwide, according to a 2013 report from Point Loma University’s Fermanian Business and Economic Institute. Another report from sustainable design firm Terrapin Bright Green, found companies that use biomimicry can reap greater revenues and have lower costs than those that don’t.

For years, large companies have increasingly employed biomimicry to solve difficult engineering challenges. Qualcomm’s Mirasol electronic device display imitates the light-reflective structure of a butterfly wing and uses a tenth of the power of an LCD reader, while Sprint worked with the San Diego Zoo’s Center for Bioinspiration to design more environmentally friendly packaging.

But developing biomimetic designs could be a steeper challenge for smaller companies. Tech startups have an estimated 90% fail rate, and biomimetic companies are no exception.

“Bioinspired innovation faces the same challenges as other forms of innovation – years of research, design and development, financial risk and market acceptance,” Terrapin Bright Green spokesperson Allison Bernett told the Guardian. “As they face increasingly rigorous testing and financial constraints, fewer technologies progress into the prototype and development stages, a typical pattern in product development.”

However, Bernett added, biomimetics can reduce the costs and difficulties of development. “Extensive prior research, a thorough understanding and a functioning model – with the living organism providing the ‘blueprint’ – can benefit a technology’s development costs by speeding up the R&D process,” she said.

The lessons of biomimicry could even extend to market politics. Portland-based business advisor Faye Yoshihara said that the disruptive nature of bioinspired products can be seen as a threat to entrenched competitors’ interests. “Market entrants need to identify mutually beneficial ways of working with industry players and points of entry into an ecosystem,” she told the Guardian.

Alternately, Yoshihara suggested, biomimetic firms could imitate the protected environments that encourage weaker species. “Innovators must sometimes create their own ecosystems to get their product or service to market,” she said.

With that in mind, the Biomimicry Institute has developed a business accelerator to help the competition’s finalists move their designs from the concept phase to the pre-commercialization stage. Over six to nine months, the program will give qualifying companies training and mentorship from experts such as Yoshihara.

Six-sided efficiency

Hexagro, another challenge finalist, has combined agriculture with the design genius of one of nature’s most famous structures. A modular aeroponic home-growing system, it is made up of individual hexagon-shaped bins that are inspired by bees’ honeycombs.

Designer Felipe Hernandez Villa-Roel wanted his product to circumvent some of the environmental problems associated with large scale agriculture, such as carbon emissions, pesticide use and fertilizer runoff. His solution was to make it easier for people living in small urban spaces to grow pesticide-free food at home.

“I wanted to solve this problem as efficiently as possible,” he said. “And since many people can’t spend the time to garden, it needed to be something that wouldn’t take up a lot of personal time.”

The bins – which can grow lettuce, carrots, cilantro, spinach, herbs and even potatoes – evoke the resource efficiency of a beehive. They can be stacked to fit any available space. And, because the plants’ roots are in the air, they can be misted with a nutrient solution placed on an automatic cycle. Hernandez Villa-Roel claims that his pods can cut down water use by 90% compared to traditional farming.

The designer hopes that Hexagro could help decentralize food production and provide an economic opportunity for growers, who can sell their excess produce. He envisions a community of growers and distributors bringing locally grown produce to market, cutting down on the CO2 emissions commonly associated with food transportation.

“This system could also be used in Syrian refugee camps to grow food, or with the disabled or elderly,” he said. “The social consequences of this project are much greater than the project itself.”

Taking it underground

A team of students from the landscape architecture department at the University of Oregon in Eugene designed the Living Filtration System, an agricultural tool that imitates filtration processes used throughout nature. Designed to reduce fertilizer and chemical runoff from farms, the system is a new spin on traditional tile drainage systems designed to remove excess moisture from the surface of the soil.

“A [drainage] pipe made out of renewable material that mimics an earthworm’s villi to slow down runoff is one of the major components,” said Wade Hanson, a member of the team.

The students say that their drainage system also incorporates the mechanism used by wetlands to filter pollutants from water. Next fall, they will join the seven other finalists when presenting their prototype to judges in a final round. Teams will be evaluated based on a number of criteria, including proof that their technology works, the feasibility of bringing their product to market and validation that it provides a solution that customers will use.

The winner will take home $100,000 in prize money provided by the Ray C Anderson Foundation. It’s not clear if that will be an adequate sum for the winning team to develop their concept, considering the several years it usually takes to get a product on the market.

Still, Schuknect is optimistic. “Looking to nature for inspiration on how we live on this planet is essential to our future,” she said.

“The more we can expose both professionals and young people to the power of looking to nature and the power of biomimetic design, the sooner we’re going to get to a place where we are all working towards developing elegant solutions that support the needs of all life on the planet.”