The Guardian US/UK | October 31, 2013

These days, even the most casual observers can’t go long without hearing about yet another potentially disruptive business model hoping to redefine an industry.

But when that industry is food, it’s worth paying extra attention. Food, after all, affects everyone. And as the appetite for local food grows stronger than ever, a new crop of tech startups are moving to circumvent the industrial food system in favor of small, regional producers.

Innovative? Certainly. Disruptive? Maybe.

Founders from two promising examples, Good Eggs and Freight Farms, spoke at the Net Impact conference in Silicon Valley last week.

Farm-to-doorstep food, ordered online

Good Eggs, based in California, launched earlier this year after two years of research and testing to find unfilled needs in the food system. Co-founder Rob Spiro, an ex-Google employee, hung out with farmers, spent time on their ranches and tagged along on shoppers’ food-buying trips.

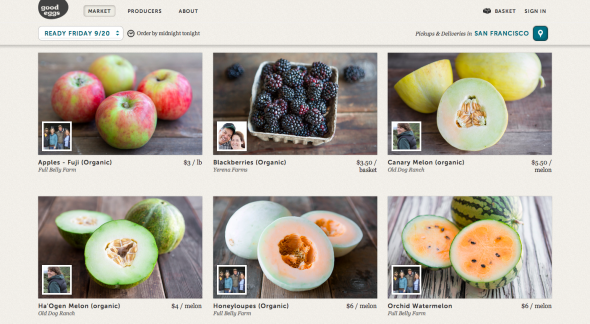

“There’s more demand than there is supply for local food … it’s very rare that you find a dynamic like that,” Spiro said at the Net Impact conference. The highly perishable nature of food, he added, causes the imbalance. Good Eggs’ solution is an online farmers’ market, complete with delivery. With more than 150 profiles of regional producers to pore through, San Francisco Bay Area residents can shop for food the way one might approach online dating.

First, find the type of product you’re interested in, whether it’s seasonal fruits and vegetables, dairy products, meats and seafood, baked goods or snacks. Then, see if the accompanying description and photos appeal to you. When you find something that meets your requirements, you can arrange to pick it up at a regional location or schedule a home delivery.

Good Eggs will aggregate orders from multiple vendors; delivery costs $3.99 per order. The idea is that shoppers have a better chance of finding what they want without having to visit multiple farmers’ markets while producers will only harvest what’s been ordered for the week, reducing food waste.

Aside from the Bay Area, Good Eggs is piloting test programs in Brooklyn, Los Angeles and New Orleans and plans to expand to hundreds of cities, Spiro said. He aims to take market share away from traditional grocers, including Walmart and Target, as well as from Amazon. “We would love to take them on,” he said.

But Good Eggs will have its work cut out to make sure it signs on enough producers to meet customer demand and vice versa. If it can’t meet most of shoppers’ grocery needs, they may not be willing to switch from bigger chains. The company also will need to keep a tight rein on quality control and – given the many different producers – make it easy for customers to choose between different products without being able to see, touch or smell them in advance.

In New Orleans, its fastest-growing market, the company already has signed on producers that weren’t previously selling at farmers’ markets, Spiro says. “We’ve got Vietnamese fishermen selling on the New Orleans [Good Eggs] market now that have not been hooked into the farmers’ markets or the local food scene,” he said.

Farm in a crate: year-round hydroponics

Two friends in Boston, Brad McNamara and Jon Friedman, were frustrated by the inefficiencies of growing plants in rooftop greenhouses. So they designed a hydroponics farm in a shipping crate that can be installed anywhere with electricity and water hookups.

That led to the founding of Freight Farms in 2010, then the raising of nearly $31,000 via Kickstarter for the company’s first unit in 2011.

The idea is a portable farm that users can use to grow local, fresh produce year round – instead of relying on food trucked or flown in from warmer climates. “Our main goal is to allow people to create small and medium-sized food businesses that can supply fresh and local foods to any environment,” McNamara, Freight Farms’ CEO, said at the Net Impact conference.

By doing that, the company hopes to ultimately change the way food is grown and distributed on a large scale. “The food system is linear, which creates inequality, access issues, price issues and spoilage,” McNamara said. “The system is ripe for disruption – and tech is a way to do that.”

Inside Freight Farms’ 40-foot-long shipping crates, users can grow their selection of more than 3,600 plants, including leafy greens, herbs and mushrooms. The system is climate-controlled, lit by LED lights and electronically monitored. Freight farmers can view the conditions in their farms via their smartphone and customize alerts, for instance, when the temperature or humidity exceeds a certain level.

The freight farms have the potential to be installed in a range of locations, such as underutilized land at schools or recreation centers, side lots or vacant lots. And, in order to use land more efficiently, the crates can be stacked four high and eight deep.

One developer in Massachusetts plans to install freight farms on three acres of an abandoned strip mall – farming a few crates himself and renting the rest to others – instead of putting in new stores. The system is designed to be accessible to those with little farming experience, McNamara claims. Inexperienced farmers have achieved crop yields of 60%, while experts have yielded 95%, he said. And the company also networks its farms so that users can support each other and share farming strategies and techniques.

Freight Farms has received a lot of interest from regional food distributors who haven’t been able to meet the demand for fresh local produce after the local growing season ends, McNamara said. “It’s cheaper for them to buy from a freight farm versus putting another truck on the road,” he added.

One distributor in Minnesota was so happy with the basil grown by a freight farmer that he offered $1.75 more per pound than the price he was initially willing to pay, he said.

With a price tag of $60,000 per shipping crate – and a threefold increase in price if the farm is solar-powered – McNamara acknowledges that a freight farm is not affordable for everyone.

In the past few weeks, though, he says he’s been exploring the ideas of regional food distributor sponsorship for crate farms in low-income communities. The distributor would pay for the farm with stipulations that a certain percentage of the vegetables would be grown for their inventory.

Freight Farms has also been tweaking its user instructions to make them more visual and to simplify the process. The hope is that this could make the farms more accessible to a broader swath of people, including those with little education or without strong English skills.

“We want to have these changes buttoned up by the middle of next year,” McNamara said.

View the original story here.