GreenBiz | November 18, 2013

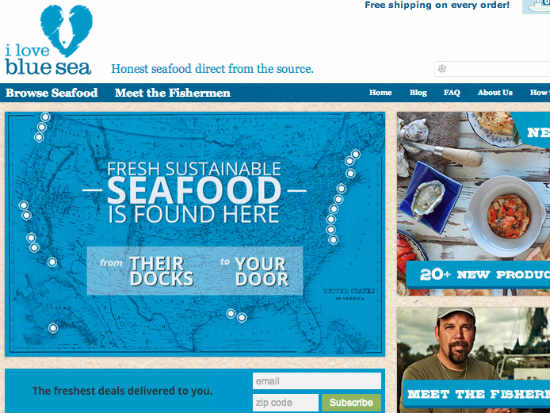

Blue Sea Labs, a San Francisco-based fish distribution company, is working to shorten the traditionally long supply chain between U.S. fishermen and the end consumer.

Traditionally, the seafood industry has not benefited either end of its supply chain. While overfishing has depleted fish stocks, fishermen have given up profit margins to large processors and distributors. And thanks to mislabeling, consumers haven’t always been too sure where their fish came from.

Now, though, access to sustainable seafood has become mainstream. Large grocery chains Safeway and Whole Foods are taking cues from the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch recommendations, and conscientious consumers try to buy directly from fishermen as much as possible.

But through new developments in technology and emerging opportunities for impact investors in sustainable seafood ventures, the movement has evolved and expanded beyond its original scope. Nonprofits such as the Future of Fish, for instance, are driving sustainability in seafood by supporting entrepreneurs.

And in the true style of startups, what better way to help entrepreneurs than by matching them up with investors during a two-day pitch session in Silicon Valley?

Scaling up

Enter Fish 2.0. Although described as a competition by founder Monica Jain, it’s also a year-long development process complete with advice and mentoring from business advisors and impact investors. Eligible entrepreneurs (those focused on wild capture-based fisheries, closed-loop aquaculture or in-ocean aquaculture systems) get the chance to refine their business models through a series of four elimination rounds with advisors experienced in finance, marketing and investing.

“These entrepreneurs offer investors the opportunity to help build viable businesses that contribute to food security, ocean sustainability and thriving local communities,” said Jain, who herself possesses a hybrid marine biologist-Stanford MBA background.

The first Fish 2.0 competition took place this year. Jain started the event as a way to bridge the gap between the entrepreneurs and interested investors who just weren’t finding viable business models. Organizers aimed to create opportunities and build momentum for impact investors in the sustainable seafood industry — a sector that has yet to seal as many deals as those in sustainable agriculture.

Through offering advice and judging during the first three rounds held online (PDF), and from sitting in the audience during the finals, impact investors got a front-row opportunity to familiarize themselves with the competitors. They were also ready to invest — some up to $10 million, according to Fish 2.0.

More than 80 hopefuls entered. Judges used a scoring system that evaluated factors such as the competitors’ business models, market conditions, financial status/projections and social and environmental impact.

By April, 53 competitors made it to the second round; in June, 39 continued to the third round. In September, 10 finalists and 11 semifinalists were chosen for the final round that culminated in the two-day event Nov. 12-13 at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif. Finalists gave a 10-minute pitch to a judging panel made up of investors and investment experts.

And the winners

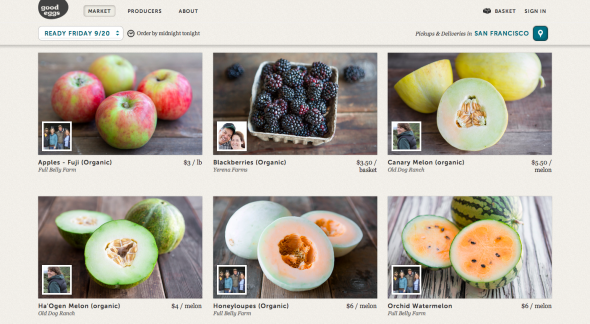

First place and a prize of $40,000 went to Blue Sea Labs, a San Francisco-based distribution business shortening the supply chain via an online system connecting U.S. fishermen to consumers. As with similar online marketplace Good Eggs, producers (the fishermen in this case) know exactly what they need to fulfill their orders and can save time and money when securing their supply.

“We are really excited about the chance to grow our business and help fishermen reach more consumers,” said Blue Sea Labs founder Martin Reed. “It was great to have a room full of investors there who wanted to know more about seafood.”

Second place went to Cryoocyte, a Harvard Innovation Lab startup that is developing fish egg-freezing technology in order to preserve endangered species for aquatic biodiversity. Founder Dmitry Kozachenok believes that freezing fish eggs also would give entrepreneurs in the developing world greater access to start their own fish-hatching operations, by providing them with a year-round supply of eggs and a way to bypass the costs of breeding and transporting juvenile fish.

“We want people to have better access to healthy foods, and we want generations down the road to have the same biodiversity in the oceans that we see today,” said Kozachenok, adding that he hoped to use his company’s technology to help restore wild fisheries. Cryoocyte received a $25,000 prize.

Ho’oulu Pacific, a community-based aquaponic and distributed agriculture business, won third place. Based in Waimanalo, a Native Hawaiian community east of Honolulu, Ho’oulu Pacific hopes to give residents the tools to establish healthy food security by growing fish and vegetables in their backyards. The integrated closed-loop system directs water flow from the fish tank to the plants. Plants extract nutrients from the fish waste, and the water is purified by the plants.

The company will buy the surplus and sell it to surrounding communities. Co-founders Keith Sakuda, Ilima Ho-Lastimosa and David Walfish aim to expand the network across the Hawaiian Islands. They received $10,000 in prize money.

In the fast-pitch competition, semifinalists had just 90 seconds to make a winning impression and $2,500. SmartFish, which aims to improve fishermen’s livelihoods in developing countries through the development of local and regional markets for sustainable seafood, tied with Inland Shrimp Company for the honors. Based in the Midwest, the Inland Shrimp Company is focused on raising shrimp indoors using sustainable methods.

View the original story here.

Screenshot of Blue Sea Labs courtesy Blue Sea Labs; image of fishermen setting their nets courtesy Loki Fish Co./Blue Sea Labs