The Guardian US/UK | December 14, 2015

Tidal Vision founders Craig Kasberg (L) and Zach Wilkinson in Juneau, Alaska. Photo credit: Alex Gaynor/Tidal Vision

Since he started working on commercial fishing and crabbing boats as a teenager, Craig Kasberg loved being out at sea. Yet he was bothered by the amount of fish waste he saw being dumped back on to the ocean floor.

“The seafood industry is behind the times when it comes to byproduct utilization,” says Kasberg, a fishing boat captain based in Juneau, Alaska. “Even though some companies are making pet food, fertilizer and fishmeal [out of the waste], there’s still a lot being thrown away.”

Every year, US fishermen throw out an estimated 2bn pounds (900m kg) in bycatch alone – an amount worth about $1bn (£660m), according to nonprofit organization Oceana.

Because the US Environmental Protection Agency does allow (in some cases) fish waste to be tossed back into the ocean, seafood processors commonly dispose fish guts, heads, tails, fins, skin and crab shells in marine waters. Once there, the decomposing organic matter can suck up available oxygen for living species nearby, bury other organisms or introduce disease and non-native species to the local ecosystem.

Last autumn, Kasberg took action. He recruited a small team of scientists and engineers. Together, they

Salmon skin leather tanned by Tidal Vision using its vegetable-based process in Juneau, Alaska. Photo courtesy Craig Kasberg/Tidal Vision

developed a vegetable-based tanning process for salmon skin. Now – a little over a year later – his company Tidal Vision has launched a line of wallets made from salmon skin leather.

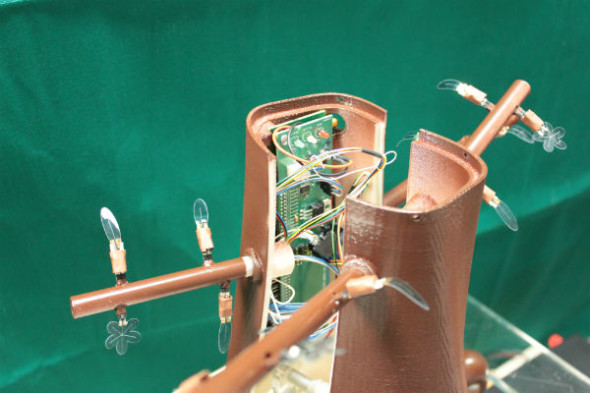

The company has also been working on an environmentally-friendly way to extract a compound called chitin from crab shells to make chitosan, which has many uses in agriculture and in medicine. The conventional method for extracting chitin uses sodium hydroxide, a caustic chemical.

Tidal Vision is getting ready to process the chitosan so that it can be turned into antibacterial yarn and fabric. One of the byproducts of its extraction process is an 8 percent nitrogen organic fertilizer, which the company is also working to bring to market.

Kasberg is part of a growing group of seafood industry entrepreneurs moving beyond fertiliser and fishmeal to upcycle the seafood industry’s waste in innovative new ways.

“Seafood is a tight margin business, so anything that can be done to reduce waste will help profitability,” says Monica Jain, founder and director of Fish 2.0, a pitching competition for sustainable seafood entrepreneurs. Finalists get exposure to potential investors and can win cash prizes. One of the winning startups at last month’s event in Silicon Valley offers a way for aquaculture farmers to turn their fish waste into algae.

SabrTech, based in Nova Scotia, Canada, took two years to develop a system called the RiverBox. Housed within a standard shipping container – picture a walk-in closet with shelves along one wall – it contains up to 10 tiers where algae grows. “Farmers pump the water [from their fish pen] straight into the RiverBox,” explains SabrTech founder and CEO, Mather Carscallen, who is finishing his PhD in ecology.

The algae growing on each tier acts as a bio-filter to purify the water, according to Carscallen, by removing nutrients – such as nitrogen and phosphorous – which the algae uses to grow. The water then goes back into the fishing pen and farmers can harvest the algae to use as fish feed or for other applications (such as biofuel, fertiliser or industrial clean-up). This, says Carscallen, creates a closed-loop aquaculture system.

Another Fish 2.0 competitor focused on waste is HealthyEarth, based in Sarasota, Florida. The company is in the process of transforming the traditional mullet fishery in Cortez, a small Gulf coast fishing village considered to be one of the oldest in the US.

“Mullet is wild caught in the Sarasota area near Tampa Bay,” says Christopher Cogan, CEO of HealthyEarth, who is a longtime entrepreneur with an interest in impact investing. “But because the fish is prized for its roe [fish eggs], the rest of it is thrown away.” Last year, HealthyEarth initiated a FIP (fishery improvement process) as a way to formally set in place sustainable policies and practices for the mullet fishery. It collaborated with Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Service, the Mote Marine Laboratory (an independent marine research institution), and local mullet fishermen to help shape the process.

In order to give fishermen financial incentive to sell more than just mullet roe (a delicacy known as bottarga), HealthyEarth wants to build an $11m processing plant that can process the roe, extract omega 3 fish oil and process the carcasses into fish meal or fish feed. The two existing local processing plants only have technology to cut the roe out, Cogan says.

HealthyEarth plans to give local fishermen the opportunity to have shares in the processing plant. Cogan says the business should pay for itself once 20 to 30 fishermen come on board. “We want to give the local guys, who follow [the FIP] rules, equity in the business,” he says. “We’ll pay them premium for the roes and the fillets.”