GreenBiz | March 27, 2013 | Original headline: How a civic app is turning city residents into agents of change

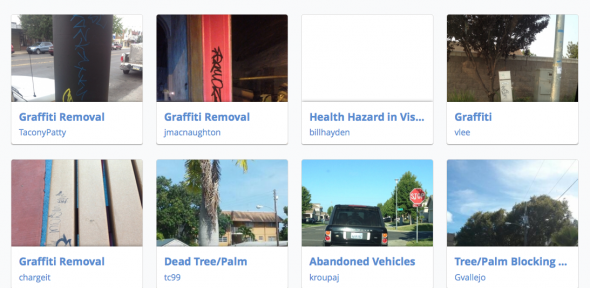

Civic improvement requests resolved via PublicStuff mobile app. Credit: PublicStuff

Would you turn in the girl next door for watering her lawn too much?

That’s exactly what has been happening in Plano, Texas ever since the city started using a mobile app and digital communications system. Residents can report problems in real-time ranging from environmental health hazards to water leaks, potholes, trash and broken street lights.

When the city’s water supply was under siege due to invasive zebra mussels and a simultaneous drought, the City of Plano restricted residents to watering their yards once a week, then once every other week. But with limited staff, there was no way the city could absorb the costs of monitoring and enforcement around the clock. Drive-bys noting whether lawn color was closer to brown than green wouldn’t cut it either.

Enter the mobile app and communications system the city purchased from New York City-based startup PublicStuff. Suddenly, residents who downloaded the FixIt Plano app (for free) could stop grumbling to their friends about their neighbor’s behavior — and gleefully send a hall-of-shame photo (which included the date and time the photo was snapped) documenting the excess water consumption directly to Plano City Hall instead. The location of the incident could also be mapped as well, provided the phone’s location tracking was on. And once the “report” was in the system, anyone could track its progress through receiving push notifications from city staff.

“When we enabled people to report watering violations, the use of our PublicStuff website and app really skyrocketed,” Melissa Peachey, the electronics communication manager for Plano, told GreenBiz.

Residents got so snap-happy, in fact, that in the first 19 days after FixIt Plano set up a category for water violations, 71 reports were filed.

“Being able to tag a picture to it makes it a valuable tool … The technology puts the reporting capability in their hands and they can make that report as they see [the issue],” Peachey said.

Though the watering restrictions have since been relaxed (residents are now allowed to water twice a week), the FixIt Plano app remains a convenient way for residents and city staff to keep an eye out for violations.

To date, the city has closed nearly 3,900 resident reports on the app since it debuted in 2011. Analyzing the data as a whole, Peachey says, enables Plano to make data-driven decisions for the benefit of citizens and city budgets. One such decision that might be made based on FixIt Plano data is where the city will spray for mosquitoes as a means of controlling potential West Nile Virus carriers. The city will map the locations of dead birds reported by residents and look out for areas of high concentration. A pop-up message informing that a dead bird was spotted, along with instructions on how to dispose of one in a safe manner, will be sent out to residents after the original report was filed, according to Peachey.

National push to use technology and open data for city problem-solving

Plano is just one of many cities using mobile technology to do a better job of tracking problems with the help of residents. These innovators are using open data collected by and from the local population to better plan emergency responses, city services and manage everyday occurrences such as traffic jams.

While about 200 cities (including Philadelphia, one of the pioneers of using open data and civic hackers for public good) have purchased the PublicStuff software and app that are customizable with widgets of their choice, others have signed up with competitors SeeClickFix and Citysourced to give residents access to city hall by reporting via their mobile devices.

In an update of PublicStuff’s mobile app released last week, non-English speaking residents can send in requests in their native language, and their message will be automatically translated into English for the city workers — and vice versa.

How’s it working so far? “We’ve gotten a lot of good feedback,” PublicStuff co-founder and CEO Lily Liu told GreenBiz. “We want to be sensitive to different words used in local languages and let people know that there are some sorts of modifications to the text. Obviously that will affect someone’s response and we’re building in a mechanism for that,” she said. PublicStuff also wants to make sure that its system recognizes colloquial words like “graffiti,” Liu added.

Increased communication between city staff and residents — along with increasing civic engagement — are not the only benefits for the multitudes of cash-strapped cities that have been forced to cut back on city services and staff in recent years. According to Liu, cities using her company’s products have been able to free up much-needed staff time from taking reports over the phone. Users can also pay their municipal bills and parking tickets on PublicStuff.

The service can also facilitate quick communication of crucial information during emergencies when power lines might be down, Liu said.

“Before Hurricane Sandy, cities sent out information on how to prepare, and during the hurricane residents sent in notes on the system rather than bogging down 911 lines, so critical resources weren’t tied up,” she said.

Liu, who was recognized in December by Forbes as a “30 Under 30” social entrepreneur, co-founded PublicStuff with Vincent Polidoro (now the company’s Chief Technology Officer) in 2010. The initial beta version of PublicStuff was released at the end of that year, and it was tested in a few cities in early 2011. The company is backed by FirstMark Capital venture capital firm and the Knight Enterprise Fund.

A former staffer for New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Liu was inspired to develop the product after noticing that there was a gap in services for government agencies that wanted a better way to communicate with the public. None of the vendors, products or price points were accessible for cities, she said.

The cost for cities to install the PublicStuff software and use an app depends on the population size — anywhere between $1,000 for small cities and “more than $20,000” for large cities, according to Liu.

Plano did not say whether it has saved money from using PublicStuff, though Adrian Hummel, the electronic media specialist for the city who works on the back end of the system daily, observed that many of the reports sent in are closed within 24 hours.

“Some remain longer,” he said. “Obviously a pothole or street repair will take longer than [picking up] a dead animal.”