TakePart | Mashable | Nov. 14, 2014

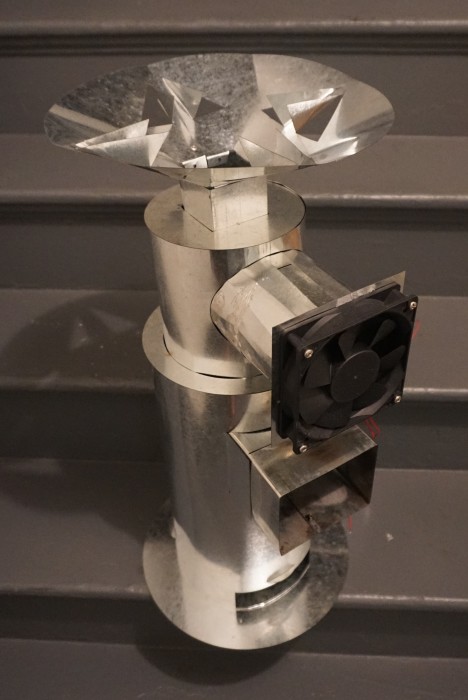

The KleanCook stove inspired the design for the K2 cookstove. Photo credit: Energant

It’s no secret that the smoke spewing from open fires and from indoor coal-fired cook stoves is a silent killer in the developing world, and a contributor to climate change. More than 4 million people die each year from health problems related to inhaling carbon monoxide or particulate matter released from stoves that burn wood, biomass, or coal, according to the World Health Organization.

Despite a long-running government campaign to eradicate dirty fuels from households, the problem persists in China. But thanks to two young entrepreneurs, a new kind of cook stove—one that can cleanly combust small amounts of plastic trash and convert its excess cooking heat to electricity—could be on its way into kitchens across China.

“Smoke-related illnesses are a bigger issue than malaria or HIV,” said Jacqueline Nguyen, one of the entrepreneurs and a University of California, Berkeley, senior toxicology student. “It kills more than HIV and malaria worldwide per year.”

While Nguyen handles business and marketing for Energant, the company behind the device, her best friend, Mark Webb—a 2011 Berkeley graduate who studied biochemistry—designed the K2 cook stove.

The K2 reduces smoky emissions by 95 percent, according to tests Webb conducted. Using the excess heat created during operations, it can generate enough electricity to trickle charge a mobile phone. It has the ability to burn biomass briquettes cleanly as well.

It can also burn plastic and wood without toxic emissions as long as the material—which emits volatile organic compounds when burned—doesn’t exceed 8 percent of the mass being used as fuel, according to Webb.

The ability to burn plastic and wood cleanly is what distinguishes the K2 model from the KleanCook stove, the product Webb designed last year.

Webb got the idea for the K2 cook stove during pilot testing of the KleanCook model in the Philippines this past summer, when he and Nguyen noticed people cooking food over open fires all across the country—and burning plastic bags as a way to get those fires started.

“We decided to make the K2, which was centered specifically around being able to burn off all of the toxic material from this trash,” Webb said.

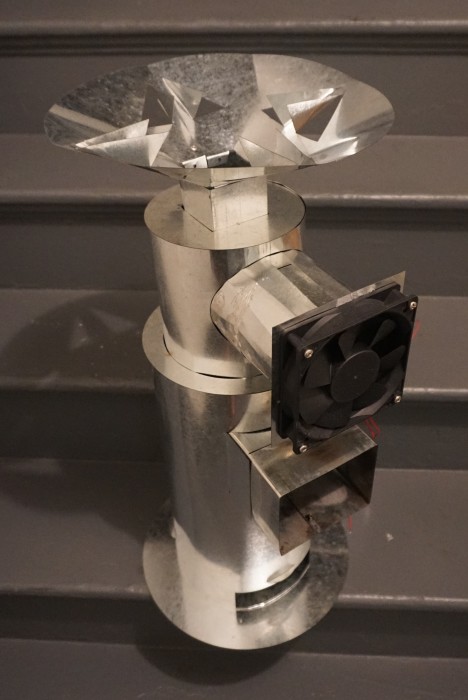

The K2 cookstove. Photo credit: Energant

But because the two wanted the cook stoves to generate income for local people who would sell the devices for profit, they decided to target the Chinese market, as business costs in the Philippines were too high.

How does it work, and what differentiates it from other clean cook stoves?

The stove’s built-in fan has a geometric design and resembles the turbo fan of a jet engine. When the fan blows air into the fire, it creates forced convection, which makes the stove more fuel-efficient. Carbon monoxide is then converted to carbon dioxide.

The stove’s greater efficiency means that 50 percent less fuel has to be burned to create the same amount of heat, resulting in lower emissions, according to Webb. A patent is pending on the K2’s design.

The stove also contains a thermoelectric generator. When one side of the device is exposed to heat and the other is kept cool, an electric current is generated as the heat travels from one side of the generator to the other. That electric charge is then fed into a voltage regulator to produce a steady current.

Because it’s made from cheap metal, the stove costs only $16 to manufacture. Energant plans to sell the stoves to regional distributors for $20 to $25. In turn, the salespeople will sell the units at retail for $50—a price that Webb and Nguyen say the Chinese government has deemed an acceptable amount to charge based on disposable income.

The debut of the K2 cook stove could be timely, as recent reports from China indicate there’s been an increase in burning trash and plastic, which releases carcinogenic dioxins.

Webb and Nguyen’s clean cook stove venture attracted support from Berkeley’s Development Impact Lab after the pair won the lab’s “Big Ideas” student innovation contest with the KleanCook stove.

The development lab is one of seven university efforts funded by USAID via the U.S. Global Development Lab. That initiative gives money to seven centers at universities around the country that support students creating solutions to global problems such as climate change, food security, health, and poverty.

“Our whole market approach to the KleanCook was to have the cheapest possible thing that was the most scalable and can deliver electricity for devices,” Webb said.

KleanCook also won prize money from the Clinton Global Initiative University contest this past year, which allowed the entrepreneurs to fund KleanCook’s pilot testing in the Philippines.

Though the K2 cook stove—KleanCook’s more sophisticated sister—appears promising, it isn’t ready for market yet. Webb says Energant has a pre-manufacturing prototype that he’s tested for efficiency using a consumer carbon monoxide sensor that recorded the carbon dioxide output of the stove.

To win the confidence of Chinese consumers, he says K2 needs to be tested using validated equipment—something that Energant would have to pay for specialists to do at Beijing’s Tsinghua University.

The company hopes to raise $30,000 from an Indiegogo campaign to pay for the testing.

View the original story here.